Legal Trends In Estate Planning 2023: Part 1

This is the first installment in a series of discussions between legal experts about the trends they’re seeing in laws relevant to Estate Planning.

Q & A with Michael Shapiro and Anne Rhodes

This is the first part of a series of discussions between legal experts about the trends they’re seeing in laws relevant to Estate Planning for 2023.

The responses have been edited for brevity.

Michael D. Shapiro, Esq. (MS)

Vice President and Wealth Planner at Brown Brothers Harriman (BBH), a financial institution with expertise in Private Banking, Investment Management, and Investor Services. In that capacity, Michael advises ultra high net worth families on complex strategies for wealth transfer and business succession. Prior to joining BBH, Michael was a practicing estate planning attorney in the New York office of McDermott Will & Emery LLP, the only Band 1 law firm in Chambers’ rankings for Private Wealth Law in the USA.

Anne Rhodes, Esq. (AR)

Vice President, Head of Legal at Wealth. Prior to working at Wealth, she was an estate planner in the San Francisco office of Perkins Coie LLP and a tax attorney in New York City. Most recently, her practice focused on complex tax planning for families with cross-border concerns and families with first-generation wealth.

Question 1: What are some common themes or trends you’ve noticed in the industry lately?

MS: Now is an intriguing time in the world of trusts and estates. States are competing with one another to attract and retain high net worth individuals and families, as well as trust and trustee business. This competition is expressed in the amount (if any) of estate tax imposed by the state and by changes to the state’s internal trust laws to make the state more “trust friendly.”

First, many states recently have either eliminated their estate tax altogether or raised the threshold value before an estate tax will be imposed. For instance, as of January 1, 2018, Delaware and New Jersey no longer impose an estate tax. Within the last decade, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, and Maryland each have significantly increased the threshold value of an estate before state estate tax will be imposed.

Second, some states have extended or eliminated the rule against perpetuities. The effect of this rule was that trusts could last about 100 years. Eliminating the rule against perpetuities permits a trust to continue indefinitely. For instance, Alaska, Delaware, Idaho, Kentucky, New Jersey, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and South Dakota permit trusts to last forever (with some states imposing certain limitations).

Other states have significantly increased the length of time a trust may last: Alabama (360 years), Arizona (500 years), Colorado (1,000 years), Georgia (360 years), Nevada (365 years), Tennessee (360 years), Utah (1,000 years), and Washington (150 years). Florida recently extended its perpetuities period from 360 years to 1,000 years.

Third, some states now allow “directed trusts.” A common directed trust structure appoints the trustee to take legal title and custody of the property, but grants investment decision-making to an “investment adviser” and decisions regarding distributions to the beneficiaries to a “distribution adviser.” The trustee is compelled to follow the directions of the investment adviser and distribution adviser and is relieved of any liability caused by the directed actions. At least 20 states permit directed trusts by statute: Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

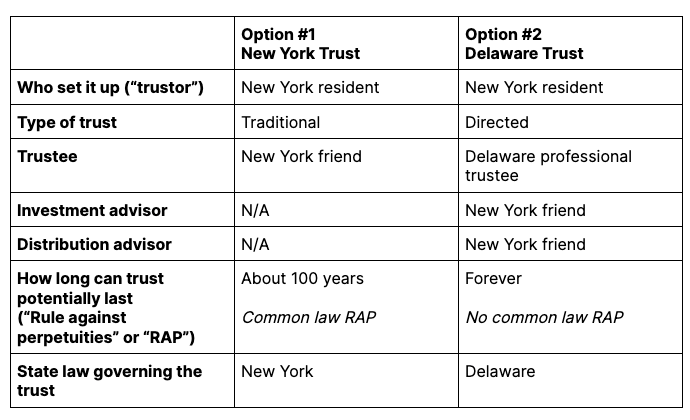

Competition for trust business among states has created greater flexibility and additional options when creating and administering trusts. For instance, assume a New York resident wants to create a trust for her descendants and to appoint a friend, also a resident of New York, as trustee. Traditionally, she would create a New York trust that would be subject to the common law rule against perpetuities. Today, she could create a Delaware trust by engaging a Delaware trust company as trustee. By forming the trust in Delaware, the trust is permitted to last forever. If she creates a directed trust, she could still appoint her trusted New York friend as the investment adviser and distribution adviser, who would make the substantive decisions regarding the trust property and distributions to her descendants.

AR: I agree with Michael that states are exploring ways to make their jurisdictions more attractive so that people move there, give business to local companies, and grow the state economies. I see more states allowing their married residents to choose to treat their assets as community property (“CP”) in the hopes that they and their beneficiaries will be able to take advantage of an income tax benefit called “basis step-up.” “Basis step-up” results in a new owner paying less income tax when selling an asset.

Having the choice to treat an asset as CP is especially helpful as folks move out of states that were traditionally CP states, like California, but want to keep that tax benefit despite moving out. The newer trend is for a state to let their residents not only keep assets as CP after they moved from another state, but to treat assets that were never CP before as such. Florida is the latest state to follow this trend, following Alaska, Kentucky, Tennessee, and South Dakota.

Question 2: Are there any major differences between how your clients think about estate planning now versus 5-10 years ago?

MS: The year 2010 brought some changes to the estate planning world. First, the federal estate tax exclusion amount increased to $5 million per person, the highest it had ever been. Every few years, there is concern that the exclusion amount will be decreased. But so far, it has continued to increase. Beginning in 2018, the exclusion amount was increased to $10 million per person (adjusted for inflation annually), and currently in 2022 it sits at $12.06 million. In 2023, the amount will be $12.92 million.

Under current law, the increased exclusion amount will sunset at the end of 2025, and the amount will return to $5 million per person (adjusted for inflation) in 2026. For clients who can afford it, we encourage them to utilize the increased exclusion amounts while they are available. It’s a real use it or lose it scenario.

Second, in 2010 a law was passed enabling a spouse to transfer any unused estate tax exclusion to the surviving spouse. This is referred to as “portability.” For some families, this makes estate planning simpler. Before portability, estate planners often recommended creating trusts under everyone’s estate plan, even for families with more modest means, to ensure they took advantage of the available exclusion amount, which used to be much lower. With the higher exclusion amounts and portability, many families determine that they no longer need to create trusts or use other sophisticated planning. Instead, they may simply leave everything to the surviving spouse, who may use both spouses’ exclusion amounts at the surviving spouse’s death. Relying on portability is not prudent for all families, and each person should discuss his or her unique situation with an estate planning attorney.

AR: To be honest, I didn’t have clients ten years ago! With the COVID-19 pandemic, I see clients paying more attention to their advance health care directives than they used to. People also feel more strongly that their religious and political identities should be represented and reflected in their estate planning documents (and particularly the advance health care directive). All of that contributes to clients thinking through in much greater detail what they would want done for or to them if they weren’t around to make their own decisions and then making sure they preserve their wishes in writing.

The advance health care directive used to be more of an after-thought. An estate planning attorney usually spends a lot more of their time drafting and reviewing with the client the Will or revocable trust agreement. After all, the will or revocable trust is the document that spells out where the client’s assets will go and who is the trusted decision-maker (i.e., executor or trustee).

Now, clients are more likely to review the advance health care directive in greater detail. The lockdown and hospital policies during the pandemic have really brought to the forefront what it means for us to be human and experience sickness and death.

Question 3: What are your predictions for the near and long-term future of laws that are relevant to estate planning?

MS: Two things: the first concerns estate tax and the second concerns novel property interests. On the estate tax, there is a loud social discourse regarding wealth inequality. There is also much disdain for “death taxes.” The combination of these competing concepts has meant that Congress can’t seem to keep their hands off of estate tax legislation. New legislation is proposed annually. We are constantly reacting to and planning around what Congress may do next. I see this uncertainty continuing.

On the novel property interests, the law surrounding certain digital assets, including email and social media accounts, photos and music, and currency and NFTs, may not be entirely settled, especially when it comes to estate planning and fiduciary ownership. I expect the rules for these types of property to solidify and for courts to become better arbiters of the process of controlling and owning them.

AR: More estate planning attorneys will have to familiarize themselves with cryptocurrency and think about how to weave this topic into their legal documents and advice to the clients after their estate planning documents are signed.

Most estate planners are now used to including digital assets as an asset class into their Wills and trusts to make sure, at a minimum, that the trusted decision-maker has the power to deal with those assets. But it may no longer be enough to make sure someone has the power to manage digital asset – you need to know whether your client owns digital assets with significant value and ensure that someone can find, access and distribute them to the intended beneficiaries. Cryptocurrencies and NFTs just highlight and exacerbate thorny issues in estate or trust administration that already existed. These types of assets are out there, and your clients own them. It’s time to get on board.

Find part 2 of this series here.

The views and opinions expressed in this article and the more fulsome responses from each expert are for information purposes only and do not constitute investment, legal, or tax advice. They are not intended as an offer to sell, or a solicitation to buy securities, services, or investment products. Views and opinions are current as of the date of publication and may be subject to change.